Note: In what I anticipate will be the last installment about the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik (Sugar Factory) located outside Ratibor, Germany, the town where my father Dr. Otto Bruck was born in 1907, I review the background and explore the German law that resulted in compensation being denied to descendants of the original co-owners of the factory. Readers will be disappointed because I am unable to clearly explain this. I will end this sequence of articles about the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik with a series of questions that remain unanswered. This post allows readers to understand the twisted path sometimes involved in retrieving and reconstructing ancestral information for one’s family, resulting in both satisfactory and unsatisfactory outcomes.

Related Posts:

Post 25: Death in The Shanghai Ghetto

Post 36: The Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik (Sugar Factory) Outside Ratibor (Part I-Background)

Post 36, Postscript: The Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik (Sugar Factory) Outside Ratibor (Part I-Maps)

Post 59: The Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik (Sugar Factory) Outside Ratibor (Part III—Heirs)

At the outset, I need to apologize to readers for the exhaustive background of how the heirs of Adolph Schück (1840-1916) (Figure 1) and his brother-in-law Sigmund Hirsch (1848-1920) (Figure 2), the original co-owners of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik (Figure 3), attempted to obtain compensation from the German government for the forced sale of the plant by the Nazis in 1936. Regular readers know I am not only a stickler for accuracy but also for sourcing my information. Unfortunately, this sometimes leads to tedious detail.

In Post 25, I discussed the fate of one of my father’s first cousins, Fritz Goldenring, who perished in the Shanghai Ghetto on the 15th of December 1943. As I explained to readers at the time, I contacted one of the Chabad centers in Shanghai hoping to obtain a copy of Mr. Goldenring’s death certificate; Chabad is one of the largest Hasidic groups and Jewish religious organizations in the world promoting Judaism and providing daily Torah lectures and Jewish insights. Almost immediately after sending emails to three centers, I received a reply from Rabbi Shalom Greenberg. He had forwarded my request to Mr. Dvir Bar-Gal, who leads “Tours of Jewish Shanghai” and has become known as Shanghai’s “gravestone sleuth” because of his tireless work tracking down Jewish tombstones scattered around the city’s outlying villages following the demolition of the Jewish cemeteries there.

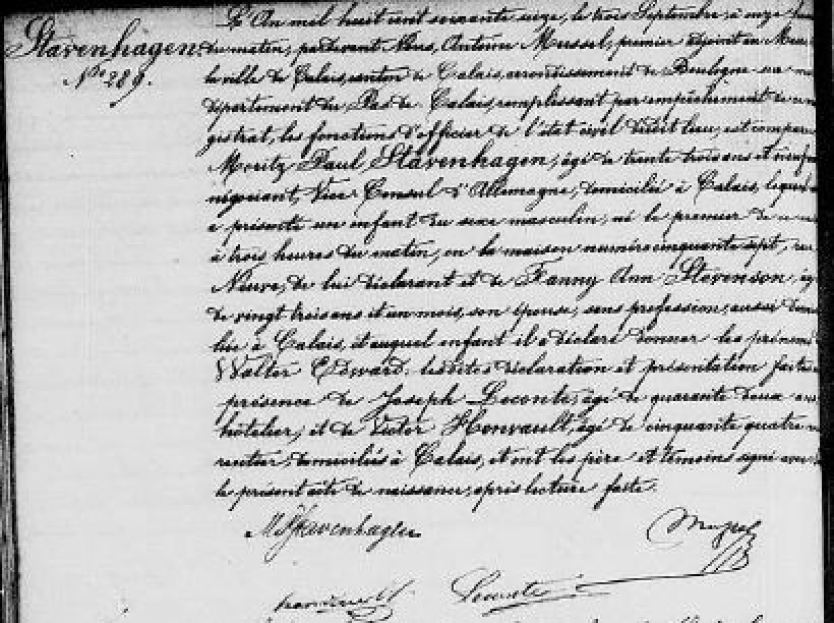

While unable to provide a death certificate for Mr. Goldenring, Mr. Bar-Gal offered useful information. He told me that before being expelled from Germany, Fritz had last worked in Darmstadt, Germany as a journalist. He suggested I contact the Rathaus (City Hall) there by email. My question to them about Fritz Goldenring was forwarded to the Stadtarchiv, or City Archive, in Darmstadt, and in October 2017 they responded. They too could not find his death certificate nor evidence Fritz Goldenring had lived in Darmstadt, but they did provide a valuable clue to an on-line directory mentioning him kept at the Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, the Hesse Central State Archive, in Wiesbaden. They also told me Fritz had been born in Berlin, and I was subsequently able to locate his birth certificate showing he was born there on the 11th of September 1902. (Figure 4)

Based on what the Stadtarchiv in Darmstadt told me, I next contacted the Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, hoping to finally obtain Mr. Goldenring’s death certificate there. While they too were unable to track it down, the archivist told me about an Entschädigungsakte, a claim for compensation file, submitted by his mother Helene Goldenring née Hirsch (Figure 5), as the heir of her son’s estate. Presumably, this was the document the Stadtarchiv in Darmstadt found mention of. After paying a fee, I was able to obtain a copy of this 160-page file, a document that ultimately filled in some holes.

The review above provides the necessary context for where this led me in March of this year. While working on a Blog post unrelated to the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik, I took the opportunity to reexamine the 160-page file the Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv had sent me in December 2017. Something I had previously deemed inconsequential caught my attention this time, namely, a reference to a file about the sugar factory numbered “Reg. Nr. 40 672.” (Figure 6)

Having no idea what this might contain or where to obtain a copy, I asked Mr. Achim Stavenhagen-Bucher, a Swiss acquaintance with greater familiarity deciphering German documents, if he could help. He suggested I contact the “Bezirksregierung Düsseldorf.” Achim explained this office was responsible for handling claims from Nazi victims of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia as well as those regions that belonged to Germany until the 31st of December 1937, based on the Bundesentschädigungsgesetz (BEG), the Federal Compensation Act; this Act encompasses three separate German laws that were adopted in 1953, 1956, and 1965. I will return to these later as it gets to the heart of why the lineal heirs of the owners of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik were denied compensation for the forced sale by the Nazis of the sugar factory in 1936.

As the source of Helene Goldenring née Hirsch’s original 160-page compensation package, I again contacted the Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv asking them how I might obtain the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik file. They referred me to the Landesarchiv Berlin, though the response from the Bezirksregierung Düsseldorf is ultimately how I tracked down and obtained the document. They told me to contact the Landesamt für Bürger- und Organisationsangelegenheiten (LABO) in Berlin, specifically their Compensation Office, the Entschädigungsbehörde. Their website describes their function:

“The compensation authority in the State Office for Citizens’ and Regulatory Affairs implements the Federal Law on Compensation for Victims of National Socialist Persecution (BEG), the Law on Compensation for Victims of National Socialism (BerlEG), the Law on the Recognition and Provision for Victims of Political, Racial or Religious Persecution under National Socialism (PrVG) as part of its responsibility for the State of Berlin.

According to the will of the federal legislature, initial applications under the BEG for recognition and provision of National Socialist injustice have not been admissible since 1969. Persons recognized as victims of persecution generally receive monthly pension benefits and ongoing, case-by-case health care benefits (curative proceedings) for established health damage because of National Socialist injustice. Each western federal state has its own compensation authority. Section 185 of the Federal Compensation Act regulates which of the compensation authorities is responsible in each individual case.

All benefits are granted only upon application. The exclusion of compensation benefits to former members of the NSDAP [National Socialist German Workers’ Party] or one of its branches goes without saying.”

I contacted LABO and had the good fortune to land upon a very helpful lady, Ms. Angela Sponholz, who sent me “Reg. Nr. 40 672” related to the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik at no charge. I will get into some of the contents of this file below.

At this point, let me briefly digress and identify Adolph Schück’s and Sigmund Hirsch’s heirs and provide some observations as to their rights to shares of the sugar factory. Except as noted below, the following analysis assumes that, upon the death of an individual, his or her share goes to the individual’s spouse; if there is no spouse upon death, it would be divided among the individual’s children; and if there is no spouse and there are no children, it would be divided among the individual’s siblings. The analysis assumes this order of distribution either under applicable intestacy laws or under the provisions of any applicable wills or trusts.

ADOLPH SCHÜCK AND SIGMUND HIRSCH’S HEIRS

| POST-1920 OWNERS | FIRST TIER HEIRS | SECOND TIER HEIRS | THIRD TIER HEIRS ** |

| Auguste Leyser née Schück (1872-1943) (1/6th) (Adolph Schück’s daughter) | Friedrich Leyser (1898-1959) (1/12th) (Auguste Schück’s son)

|

Katerina Leyser née Rosenthal (1903-1992) (Friedrich Leyser’s wife) | |

| Margot Leyser née Leyser (1893-1982) (1/12th) (Auguste Schück’s daughter) | |||

| Elly Kayser née Schück

(1874-1911) (1/6th) (Adolph Schück’s daughter) |

Franz Kayser (1897-1983) (1/6th) (Elly Schück’s son) | ||

| Erich Schück (1878-1938) (1/6th) (Adolph Schück’s son)

|

Hedwig Schück née Jendricke (1/6th) (1890-1960) (Erich Schück’s wife) | Anna Johannsen née Brügge (1897-?) (half-sister of Hedwig Schück née Jendricke)

Sophia Dalstrand née Brügge (1900-1980) (half-sister of Hedwig Schück née Jendricke)

Christian Brügge II (1902-?) (half-brother of Hedwig Schück née Jendricke)

|

|

| Christian Brügge III (~1927-?) (son of Christian Brügge II)

Helmuth Brügge (~1930-?) (son of Christian Brügge II)

|

|||

| Helene Goldenring née Hirsch (1880-1968) (1/6th) (Sigmund Hirsch’s daughter) ## | Eva Zernick née Goldenring (1/6th) (1906-1969) (Helene Goldenring née Hirsch’s daughter) | ||

| Robert Hirsch (1881-1943) (1/6th) (Sigmund Hirsch’s son) | Helene Goldenring née Hirsch (1/12th) (1880-1968) (Robert Hirsch’s sister) ##

Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch (1883-1955) (1/12th) (Robert Hirsch’s sister) |

||

| Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch (1883-1955) (1/6th) (Sigmund Hirsch’s daughter)

|

Alfred Mamlok (1874-~1960) (1/12th) (Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch’s husband)

Hans Walter Mamlok (1908-1956) (1/24th) (Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch’s son) ++

Erich Mamlok (1913-1991) (1/24th) (Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch’s son) |

|

|

| Erich Mamlok (1913-1991) (1/48th) (Hans Mamlok’s brother)

Helene Goldenring née Hirsch (1880-1968) (1/72nd) (Hans Mamlok’s aunt) ##

Alfred Mamlok (1874-~1960) (1/144th) Hans Mamlok’s father)

|

|||

** Only those third-tier heirs who are known to have received “damages” from the German government in connection with the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik are shown.

++ When Hans Mamlok died in 1956, he left ½ of his shares to his brother Erich Mamlok, 1/3rd to his aunt Helene Goldenring née Hirsch, and 1/6th to his father Alfred Mamlok

## Helene Goldenring née Hirsch was an owner in her own right, as well as a first-tier heir as inheritor of a one-half interest in her brother’s 1/6th share in the sugar factory, as well as a second-tier heir of 1/3rd of her nephew Hans Mamlok’s 1/24th share

A few observations.

Adolph Schück (Figure 7) and Sigmund Hirsch (Figures 8-9) each had three children, each of whom was a shareholder with a 1/6th share of the sugar factory. Assuming the German government paid compensation or damages, each owner would have been eligible for 1/6th of the amount paid out.

In the case of Frieda Mamlok née Hirsch who pre-deceased her husband Dr. Alfred Mamlok, I would later learn ½ of her 1/6th share went to her husband while each of her two sons, Hans and Erich, received one-quarter of her 1/6th share. Hans pre-deceased both his brother and his father, and he divided what amounted to his 1/24th share among his brother (one-half), his aunt (one-third), and his father (one-sixth). My apologies if I’ve confused readers.

Figure 10 is a screen shot from my family tree on ancestry.com with Erich and Hedwig Schück née Jendricke and their heirs.

Readers can see on Figure 6 there is another file at LABO with a different number, namely, “Reg. Nr. 160 800,” for Robert Hirsch (Figure 11), one of the six heirs of the sugar factory. I would later learn there exist multiple files with unique identifiers for the various claimants.

In Post 55, I discussed at length the documentation I received from Mr. Allan Grutt Hansen, a gentleman from Denmark related to the wife of Dr. Erich Schück (1878-1938) (Figure 12), Hedwig Schück née Jendricke. (Figure 13) I refer readers to that post for details. Suffice it to say that according to the documentation I received from Mr. Hansen, several of Hedwig’s relatives in fact received some monies from the German government in connection with sale of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik in 1966. Figure 14 gives their names and their presumed inherited ownership shares of the sugar factory.

Anna Johannsen née Brügge and Sophia Dalstrand née Brügge were Hedwig Schück’s half-sisters, Christian Brügge II was her half-brother, and Christian Brügge III and Helmuth Brügge were his sons. None of the documents I’ve obtained show Hedwig’s half-brother receiving any monies in connection with the sale of the sugar factory, so he may have been deceased by 1966. The names in red text in the table above are the four heirs who each were awarded damages through their kinship to Hedwig Schück. In the aggregate, Hedwig Schück’s heirs should have inherited her 1/6th share in the sugar factory but according to the figures shown in Figure 14, the amounts total 1/4th (i.e., 1/12th + 1/12th + 1/24th +1/24th =6/24th), so something is amiss.

I naturally assumed that if Hedwig Schück’s heirs had received damages for the forced sale of the sugar factory, so too had heirs of the other shareholders. To date, I have not been able to confirm from third- or fourth-tier heirs that this ever occurred.

Readers will note in the table above that one of Sigmund Hirsch’s daughters is Helene Goldenring née Hirsch, the very same person who did receive compensation from the German government because of her son’s premature death in the Shanghai Ghetto. This was indirectly a result of Nazi pressure on the Japanese to eliminate Jews living in this occupied part of China. Rather than exterminate them, however, the Japanese incarcerated them in a ghetto under deplorable living conditions causing many to die.

Hoping to round out my understanding of how the reparations claims were handled by the then West German government, I contacted Dr. Robert Mamlok (Figure 15), the grandson of Dr. Alfred Mamlok (1874-~1960) (Figure 16), the spouse of one of the six original shareholders. Robert generously shared copies of numerous letters penned by his grandfather, the other heirs, and the multiple attorneys involved in the compensation case. Most usefully, Robert sent me a summary in English of the contents of the various documents, which precluded my having to tediously retype and translate the original German documents. With this synopsis, I came away with a much more in-depth and nuanced understanding of the years-long effort undertaken by the various claimants to obtain compensation for the forced sale of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik.

I cannot do justice to all that is contained in the correspondence Robert Mamlok shared, but I want to highlight a few things. There were some administrative challenges faced by the claimants. As alluded to above, the Berlin Compensation Office, the Entschädigungsamt Berlin, assigned unique case numbers to each claim. Each claimant had their own attorney, at times interfering or working at cross-purposes to one another. Several attorneys died over the course of the multi-year effort requiring aging and ailing litigants to begin anew with different lawyers. The claimants themselves could not agree on the amount of lost income they’d incurred because of the forced sale of the sugar factory; widely divergent estimates of annual proceeds were proffered by the shareholders (i.e., ranging between 20,000 Reichmark (RM) and 100,000 RM annually with a RM having an estimated nominal exchange rate during WWII of $2.50). Without surviving documents to bolster claims of lost income, including the sales documents of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik, lawyers repeatedly questioned the estimates and asked for less inflated figures. This further delayed the adjudication process and allowed claimants to be played off against each another. There were seemingly endless requests for supporting evidence such as powers of attorney, proof of Jewish origins, proof of residency, attestations of one’s professional practice, estimates on the value of the business and the annual profits, etc., some of which could only be recreated from fading memories.

From a cursory examination of the summary papers forwarded by Robert Mamlok, the requests for compensation were based on several considerations, namely, forced sale of the sugar factory at less than fair market value (taking into account “goodwill”); loss of professional wages; and loss of income based on the boycotting of the Jewish-owned Zuckerfabrik. (Goodwill is a marketplace advantage of customer patronage and loyalty developed with continuous business under the same name over a period. It may be bought and sold in connection with a business, and the valuation is a subjective one.) Interestingly, yet another recompense that could be claimed was the travel costs of being forced to flee Germany.

At some point, it appears lawyers representing some of the claimants made the decision it would be easier to argue loss of income due to the boycott of the Jewish-owned sugar factory by Aryan-owned businesses rather than the losses due to forced sale of the business at a discounted price. Possibly, the lawyers felt it would be easier to compare the decline in the estimated annual profits from before to after the boycott was implemented than estimate the fair market value of the business in 1936.

While the compensation claim based on the forced sale of the sugar factory continued, this was never successfully adjudicated by any of Adolph Schück or Sigmund Hirsch’s heirs. Dr. Alfred Mamlok eventually did receive some recompense for professional damages in connection with the loss of his medical practice in Gleiwitz, Germany [today: Gliwice, Poland], including possibly for the loss of goodwill, as well as payment for his costs to flee Germany. However, Dr. Mamlok did not receive payments for the loss of goodwill in connection with the sugar factory. Additionally, Dr. Mamlok, his son Erich Mamlok, and his sister-in-law Helene Goldenring received monies in 1957 but the basis for these payments is also unclear.

The summary sent to me by Robert Mamlok provided further background on the sale of the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik. Following Hitler’s attainment of power in March 1933, the responsibility for oversight of businesses like the sugar factory was transferred from the Reich Ministry of Economics to the auspices of the more stringent Reich Ministry of Food and Agriculture, making ownership and management of exclusively Jewish-owned enterprises more difficult.

Additionally, according to Dr. Alfred Mamlok’s correspondence, Upper Silesia, where the factory, was located was deemed to be an “animal welfare area.” This is a particularly interesting provision I needed to ask one of my German cousins about since I could not understand how animal welfare related to the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik. On page 256 of the 1997 German edition of the book entitled “German-Jewish History in Modern Times, vol. 4: Renewal and Destruction, 1918-1945,” my cousin found the following explanation:

“Only in Upper Silesia, on the basis of a German-Polish agreement of 1922, did the approximately 10,000 Jews living there succeed in securing special status of a protected religious and ‘racial’ minority under the protection of the League of Nations Commission until July 1937. This was the only case in which a Jewish representative body, the Upper Silesian Synagogue Association, concluded agreements with the German government in open negotiations and before an international body. As a result, discriminatory measures against Jewish gainful employment or against kosher slaughter were not implemented here until July 14, 1937.”

Thus, ostensibly under the guise of safeguarding animal welfare, the Nazis were really targeting kosher slaughter of farm animals, and limiting, where possible, Jewish economic activities including at the sugar factory. Not only did the Nazis strive to expel Jews and deprive them of their economic existence, but according to their twisted logic expropriation of Jewish businesses served animal welfare. However, it is not apparent to this author the connection between animal welfare and the manufacture and sale of sugar.

As to the sale of the sugar factory, the owners eventually found a buyer in the form of an East German sugar company which obtained the necessary approvals clandestinely. The sale papers were presented to the Reich Ministry of Agriculture when key officials there attended a congress in Nuremberg in 1936, making it easier for the buyers to obtain approval. According to one letter found among Dr. Alfred Mamlok’s papers, the sugar factory was sold for approximately 800,000 RM though the writer estimates the fair market value of the business was several million RM. As a quick aside, this figure does not comport with the number I found in the papers sent to me by Allan Hansen which based damages on a sales price of 450,000 RM.

Let me turn now to a discussion of the act which guided the compensation claims for the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik. Compensation for the victims of National Socialist injustice was governed in principle by the Federal Act for the Compensation of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution (Bundesentschädigungsgesetz or BEG) as amended by the Final Federal Compensation Act of the 14th of September 1965.

Below is a succinct description of this act from the Wollheim Memorial (www.wollheim-memorial.de/de/bundesentschaedigungsgesetz_1956):

“In July 1953, using the term Bundesergänzungsgesetz (Federal Supplementary Law), the German Bundestag passed the first national-level compensation law for people who were forced to undergo expropriation, forced labor, deportation, and imprisonment in camps during the Nazi era. In 1956, it was amended and renamed the Bundesentschädigungsgesetz (BEG, Federal Compensation Law), owing to numerous interventions by the Western Allies and the Claims Conference, which were directed primarily at the meagerness of the benefits intended for victims of the Nazis and at the exclusion of foreign victims of Nazi persecution. But the BEG held fast to the so-called subjective and personal territoriality principle, according to which benefits could be claimed only by victims of the Nazis who were residents of the FRG [Federal Republic of Germany] or West Berlin on the effective date of December 31, 1952 (originally, January 1, 1947), or had lived within the 1937 borders of the German Reich and taken up residence in the FRG or West Berlin by the effective date. From the outset, therefore, the provisions excluded from compensation all those people in the countries occupied by Germany during World War II who had been hunted by the death squads of the Wehrmacht and the SS and had not left their home countries.”

The Claims Conference refers to the Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany founded in 1951 as a coalition of several Jewish organizations to represent the compensation claims of Jewish victims of National Socialism and Holocaust survivors.

A 2009 paper prepared by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Finance, entitled “Compensation for National Socialist Injustice,” provides more detail:

“The first compensation act covering the entire [German] Federation was the Additional Federal Compensation Act which was adopted on 18 September 1953 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 1,387) and entered into force on 1 October 1953. Although this was much more than an addition to the Act on the Treatment of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution in the Area of Social Security and in particular created legal equality and security on federal territory, its provisions also proved inadequate. Following very detailed and careful preparation, the Federal Compensation Act (Federal Law Gazette I p. 562) was adopted on 29 June 1956 and entered into force with retroactive effect from 1 October 1953. This Act fundamentally changed compensation for the victims of National Socialism and introduced a number of amendments improving their situation. At the outset, the Federal Compensation Act only provided for applications to be submitted until 1 April 1958.”

The Act on the Treatment of the Victims of National Socialist Persecution in the Area of Social Security was an act adopted by the Southern German Länder Council for all Allied occupation zones. This was promulgated by Land laws in Bavaria, Bremen, Baden-Württemberg, and Hesse in August 1949.

The Federal Compensation Act was amended in 1965. Quoting again from the paper by the Ministry of Finance:

“In applying the Federal Compensation Act, further need for amendment became clear. There was an awareness that the new piece of legislation would not be able to take account of all the demands of those eligible for compensation and that, given the high number of settled cases, these could not be re-opened. The amendment was thus to constitute the final piece of legislation in this field. After four years of intense negotiations in the competent committees of the German Bundestag and Bundesrat, the Final Federal Compensation Act was adopted on 14 September 1965 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 1,315), its very name emphasizing that it was to be the last.”

A few comments.

The Final Federal Compensation Act extended the original deadline of the 1st of April 1958, though no claims could be filed after the 31st of December 1969.

Numerous provisions of the Federal Compensation Act were complicated. One decisive criterion was the residence requirement. Those eligible to apply were persecutees of the Nazi regime who had resided in the Federal Republic of Germany or West Berlin by December 31, 1952 (previously January 1, 1947), or who had lived there prior to their deaths or emigrations. Except for Dr. Alfred Mamlok, who was a doctor in Gleiwitz in Upper Silesia, all the other heirs had lived in Berlin or what became the Federal Republic of Germany prior to emigrating or being murdered, so this would not seem to have been an exclusionary criterion for receiving compensation.

As an aside, for people persecuted because of so-called “antisocial” behavior, including the Sinti and Roma, “. . .the latter, the Federal Supreme Court (BGH) claimed in a decision in principle on January 7, 1956, had been persecuted not for ‘reasons of race, religious belief, or worldview’ (§ 1 BEG) but for their ‘antisocial traits.’ The BEG believed race-based persecution occurred only from 1943 on, when the Sinti and Roma began to be sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp.”

Communists also could not receive compensation because they were perceived as alleged enemies of the “liberal-democratic basic order.” Homosexuality was a criminal offense in the Federal Republic of Germany until 1973 so for this reason persecuted homosexuals similarly were ineligible to receive payments.

After the enormity of the crimes the National Socialists had perpetrated against humanity came into the public eye and shocked the world, the willingness of Germans to accept political and moral responsibility waned. Over time, and against the backdrop of post-war reconstruction, the Cold War, and the suffering the Germans had also experienced during and after the war, many began to see themselves as the victims. Feeling they had been manipulated and terrorized by the Nazis and Adolf Hitler allowed many Germans to displace any complicity in Nazi crimes. Consequently, as German Wikiwand notes: “People began to offset their own suffering against the persecution of Nazi victims—the cliché of well-off Nazi victims became a kind of political myth—and along with the integration of former Nazi officials into postwar German society, it was not the perpetrators but the victims who were perceived as a burden on the new society.” How rich.

Given the complexity of the Federal Compensation Law, it is not clear that if the compensation cases were being adjudicated today the decisions would be rendered any differently. But readers should know that many claims were being handled by former Nazi officials, such as judges and district attorneys, who had been integrated back into German society following WWII, officials who seemingly had little interest in compensating Jews they had once so avidly been an integral part of persecuting.

File Reg. Nr. 40 672 obtained from LABO was the restitution claim refiled for the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik by Dr. Alfred Mamlok’s lawyers, Dr. Hans Zilesch and Ms. Gisela Maresch-Zilesch, for him as an individual. Contained within this file is a decision letter dated the 30th of January 1962 to his lawyers, ostensibly from the Berlin Compensation Office, laying out the reason his compensation claim vis a vis the sugar factory was denied. Followers can read the original and translated versions of this 1962 letter below. (Figures 17a-b)

In citing § 143 and § 146 of the BEG, the Berlin Compensation Office makes it abundantly clear that the claims were rejected because the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik had its registered office in Woinowitz in Upper Silesia in an area they declared was decidedly outside the scope of the BEG. I include the language of both subsections below:

§ 143

(1) The right to compensation exists only if the legal person, establishment, or association of persons

1. on 31 December 1952 had its seat within the scope of this Act or the place of its administration was situated there,

2.before 31 December 1952, for the reasons of persecution under § 1, had transferred its seat or its administration from the territory of the Reich to a foreign country in accordance with the state of 31 December 1937 or the territory of the Free City of Gdansk.

(2) If a legal person, institution or association of persons no longer exists, the claim for compensation shall only exist if it had its registered office or the place of its administration in the territory of the Reich in accordance with the status on 31 December 1937 or in the territory of the Free City of Gdansk and if the registered office or the place of administration of a legal successor or successor to a purpose was in the area of application of this Act on 31 December 1952.

§ 146

(1) The right to compensation exists only for damage to property and for damage to property and only to the extent that the damage occurred within the scope of this Act. In the case of non-legally capable commercial companies whose all partners were natural persons at the time of the persecution, the claim for compensation also exists if the damage to property or assets in the Reich territory occurred as of 31 December 1937 or in the territory of the Free City of Gdansk.

(2) Communities which are institutions of or recognized by religious communities and whose members have undertaken to acquire through their work not for themselves but for the community may also claim as damage to property the damage caused to the community by the loss of the working activities of their members. A Community national shall not be entitled to compensation for loss of professional progress in respect of any work carried out by him on behalf of the Community if the Community has received compensation in accordance with the first sentence.

(3) No compensation shall be paid for losses of contributions, donations, and similar income.

Woinowitz was part of the German Reich in 1937. In a referendum held in Upper Silesia on the 20th of March 1921, people there voted to remain part of the German Reich. On this basis, I would have assumed that Woinowitz met the seat requirements under BEG as of 31 December 1937. Whether its location inside Poland by 31 December 1952 is relevant is not clear. Regardless of my understanding of the provisions and exclusions of the complicated Federal Compensation Law, the Berlin Compensation Office determined the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik was outside the seat requirements of the act and for this reason denied compensation to heirs of the shareholders.

A separate page in File Reg. Nr. 40 672, dated the 27th of January 1964, gives the Berlin Compensation Office claim number, “Reg. Nr. 21 879,” for Erich and Hedwig Schück’s heirs, identifying them by name. (Figure 18) Attached to this cover page is the decision letter rendered by this office. Like the one sent to Dr. Alfred Mamlok’s attorneys it comes to the same conclusion, namely, that the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik is outside the seat requirements of the Federal Compensation Law. This letter came as a surprise to me. Whereas I had assumed the monies Hedwig Schück’s heirs had received were the result of a different decision rendered by the Berlin Compensation Office under the authority of the Federal Compensation Law, this letter made clear this was not so.

With this new information in hand, I returned to the eight pages sent to me by Mr. Hansen for his ancestors discussing monies paid out to them in 1966. After translating these documents, I realized there was no mention of the Federal Compensation Law and instead payments made in 1966 to Hedwig Schück’s heirs were for “damages” paid out under what I eventually learned was the “Equalisation of Burdens Act (Lastenausgleichsgesetz)” of 1952 and decided by an order from a Federal Administrative Court. Suffice it to say, at the risk of further overwhelming readers with more detail, that the difference between what Dr. Erich Schück received from the September 1936 forced sale of the sugar factory, estimated to be 75,000 RM (i.e., calculated by the Ratibor Tax Office for each 100 RM of share capital at 190 RM, thus totaling 140,000 RM), and what he should have received (i.e., 142,500 RM), his wife’s heirs were in aggregate eligible for only 2,500 RM or whatever the 1966 equivalent was in German Marks. (Figures 19a-b)

At long last, I conclude my series on the Woinowitz Zuckerfabrik saga with some questions or issues still unresolved:

1). While I assume ALL six shareholders received equal portions of the 450,000 RM (i.e., 75,000 RM each) for which the sugar factory sold for in 1936, no documentation survives to know whether this was the case.

2). While we know that Hedwig Schück’s four heirs in the aggregate divided 2,500 RM in damages in 1966, we don’t know whether the heirs of the other shareholders received equal amounts. The office in Lübeck, Germany that handled the case has no documentation on file to answer this question.

3) And, finally, given that Woinowitz was part of the German Reich in 1937, why was it deemed that it was outside the scope of the Federal Compensation Act?

REFERENCES

Barkai, Avahram, Paul Mendes-Flohr, and Steven M. Lowenstein. German-Jewish History in Modern Times. Vierter Band 1918-1945. Munich, 1997.

Federal Ministry of Finance (Germany), Public Relations Division. Compensation for National Socialist Injustice. 2009, canada.diplo.de/blob/1106528/becf2995e860c6348a1efe7b3367ce51/information-on-compensation-federalministryoffinance-download-data.pdf